-

Welcome To Condor Pictures Online !

- lm@condor-pictures.com

Welcome To Condor Pictures Online !

Condor Pictures manages and co-ordinates all aspects of a program’s life, including developing original ideas; purchasing literary rights; carrying out production and post-production.

Films can be watch On Demand (VOD) Streaming

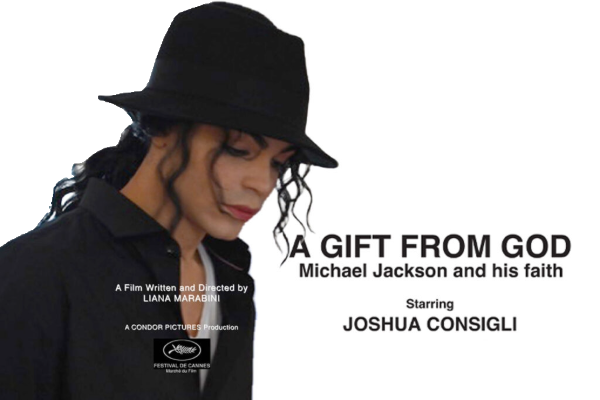

Written and directed by filmmaker Liana Marabini, the film ‘A Gift From God’ aims to shed light on a virtually unknown aspect of the King of Pop, narrated in the film during a particular moment of his life, from 1982 to 1989, the era when hits like ‘Thriller,’ ‘Billie Jean,’ ‘Bad,’ and other major successes dominated the world charts…

Read More

Packed room and enthusiastic applause for the film “A Gift from God” screened as a world premiere on May 14th at the Cannes Film Festival. Journalists from 20 countries were present as well as cinema owners, TV directors and radio managers. I did this film as an act of justice in memory of a great artist, whose spirituality and kindness was exemplary, not to mention his talent, a true and authentic “gift from God” as he himself stated, since years later he continues to still be an inspiration to many young people.

Read More

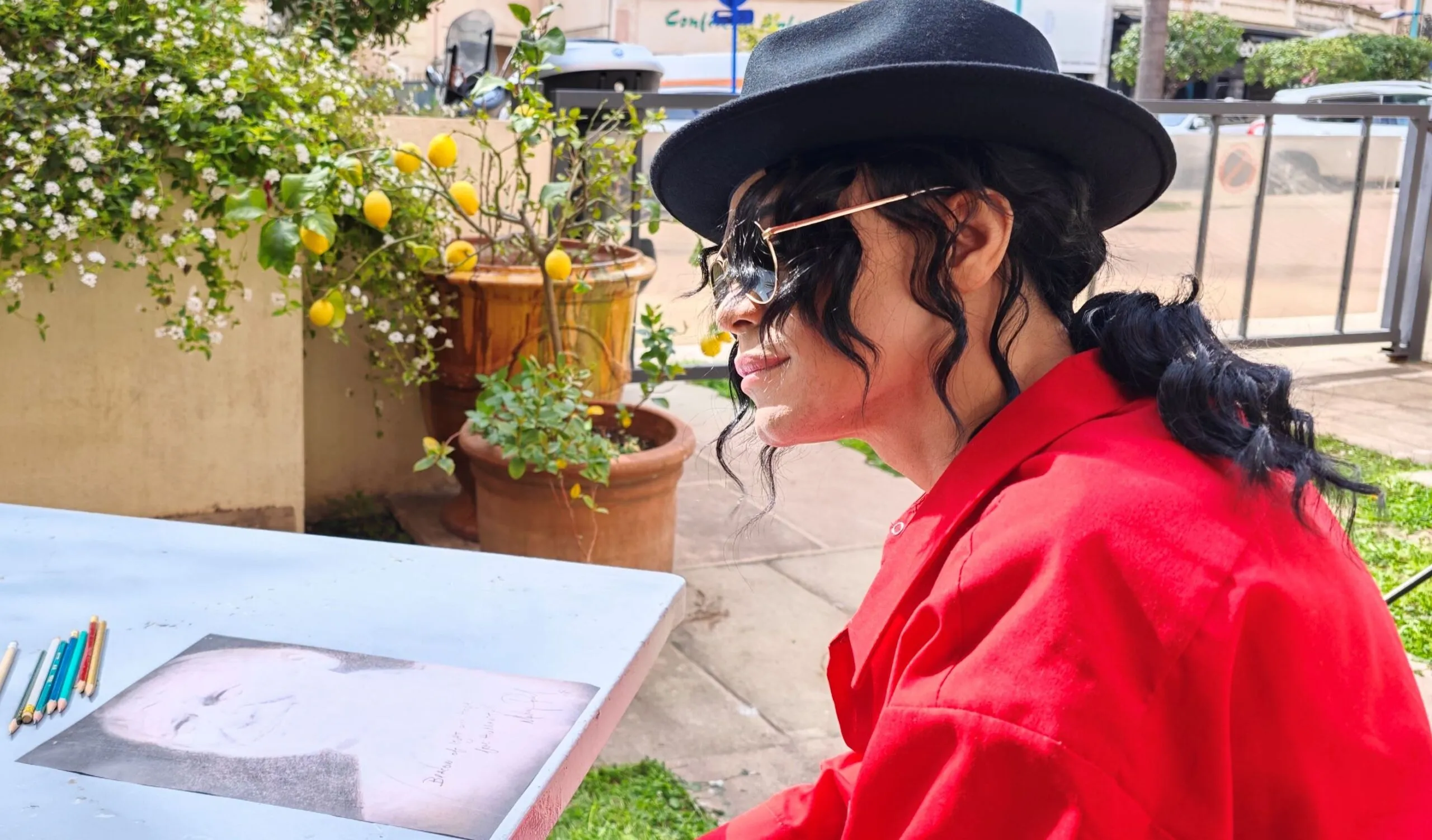

TMentone – “A Gift From God” è un film, che si prefigge di svelare il viaggio spirituale di Michael Jackson, leggenda del pop scomparsa nel 2009, e la sua “ricerca di una connessione più profonda con il divino”, come ci mostrano le fotografie scattate durante le riprese e quella che lo mostra mentre realizza un ritratto di Papa Giovanni Paolo II.

Read More